I’ve been to precisely one gay wedding. Perhaps that means I don’t have enough gay friends – or at least enough who are interested in getting married. Very possible.

The only one was ten years ago, D.C. in October. I didn’t know the men; I was a plus one for my then-boyfriend who also barely knew them, two military guys who’d just moved to town for work. The ceremony was held outdoors, at the DC War Memorial, a covered white gazebo on Independence Avenue. It was cold and rainy that morning and I remember thinking that someone was likely to slip on the slick stone floor.

The crowd was like 15 or 20 thick, max. The mutual friend who had invited my then-boyfriend greeted us and thanked us for coming. She introduced us to one of the groom’s parents, quiet, tired-looking people who had come in from North Carolina, and who couldn’t smile longer than a few moments. The mother looked like she had been crying.

We took our seats and I whispered to my then-boyfriend if I had been imagining things or did they seem really unhappy? I was, he assured me, not imagining it. To their credit, I suppose, they had shown up; the other groom’s parents did not.

The ceremony was heartfelt, if not efficient. 15 or 20 minutes in the cold fall morning and then an announcement that they would be meeting at Judy’s Salvadoran restaurant in about an hour. The mutual friend of my then-boyfriend implored us to come! It would be fun. Casual, but a nice celebration. He nodded and said we’d try to make it.

We were out of earshot, trying to hail a taxi in the rain, when I told him that I would not be going to the reception. He agreed. The ceremony itself was awkward – first by it being so small and mostly made up of what seemed to be close friends and family, but also because the groom’s parents looked miserable; the friends confused; the grooms relieved to have it all over with.

Perhaps the mother wasn’t crying out of misery. Mothers do cry at weddings, after all. And perhaps the other groom’s parents hadn’t been able to make the trip because of money or bad backs or an unrelated estrangement. Maybe none of it had anything to do with the fact that their son was marrying someone else’s son.

But I don’t believe that. I knew that it was (even, is) well within the realm of logical explanations that the groom’s parents could look so pained because they were asked to witness their son’s gay marriage (which was still illegal in half the country at that point). That cold morning in Washington, D.C. was not what they had in mind for his wedding when he was born all those years ago. My then-boyfriend had jumped to the very same conclusion. So did most of the gay people who I relayed that story to afterwards. They’d shake their heads in a knowing disappointment, a scene they’d always feared, now having come true for someone else. “They should have just stayed home,” they’d invariably say. Who could argue with that?

I adore Ang Lee’s film, The Wedding Banquet (1993). I showed it to Dallas when we were still living in Atlanta, and he loved it, too.

A charming romcom, it was made during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The epidemic reaches into various parts of the film, though the film practically never mentions it, at least not verbally. It tells the story of two men, Wai-Tung, a Taiwanese American yuppie, and Simon, a white ACT-UP activist/chiropractor, and the changes to their lives when the closeted Wai-Tung agrees to participate in a sham wedding to help secure a green card for Wei Wei, a Chinese artist living in one of Wai-Tung’s Brooklyn slum apartments. It’s a win-win in their minds. Wei-Wei stays in the country; Wai-Tung’s parents can finally drop their pressure for him to find a Chinese woman to marry. When Wai-Tung’s parents announce a trip to New York City from Taiwan to witness the wedding, it becomes increasingly difficult, even impossible, for Wai-Tung to keep his queerness away from his parents, but also keep his filial duty away from what he’s carved out to be his gay American dream.

I’ve always respected the film because I think it really cost something to make it. Money-wise, the budget was actually only around $750,000. But this was 1993 and only Ang Lee’s second feature. It would not have been unreasonable for him or Winston Chou, the actor who plays Wai-Tung, to say that making it in Hollywood as heterosexual Asian-American men was hard enough, much less risking any of that creative capital on a queer film – and one that treats queer characters with dignity and respect, no less. It was a gamble for them to make this movie. Luckily for them, it definitely paid off. The film ended up being nominated for Best Foreign Language Picture at the Oscars that year and made a lot of money. In Taiwan, it became the highest-grossing film ever at the time.

It had been on my mind to watch the film again for this newsletter, and it became increasingly pressing because in the last week … my partner and I got engaged!

It was a lovely moment, just the two of us. Some music, our balcony, my birthday. We’ve told our friends and family, and everyone has been really happy for us. Most importantly, we’re really happy for us. No idea as to when, but it’s official. We will be getting married.

So, to celebrate the nuptial mood, I revisited Lee’s film.

The Weight of Success

The film opens with Wai-Tung at the gym, his mother’s voice – recorded on cassette and sent in lieu of long letters due to a shoulder injury – speaking into his Walkman headphones. He squats, heavy weight on his back and shoulders, as his mother asks when he will finally settle down.

It becomes clear that Wai-Tung comes from a wealthy family in Taiwan. His father is a General who has also invested in Wai-Tung’s Williamsburg apartment building. Wai-Tung has a bit of a commander’s presence, himself, at his fledgling real estate development office. He seems to be following the same script that so many overachieving gay boys who become ambitious high-achieving men follow. He will excel and succeed at every level to immunize himself from being surveilled or abandoned. He has grown up, taken care of his own affairs, and can send home more-or-less true updates about how he is building an American dream. They need not worry, and they certainly need not ask further questions.

It’s true that Wai-Tung represents the hopes of his parents, but despite his success he still has not fulfilled that promise. A wealthy businessman in America is nice, but he needs to cement their legacy by providing them with a grandchild. The weight of knowing that he cannot fulfill that responsibility – perhaps the only one he cannot fulfill, and the one that matters most for his parents – must feel so lonely.

Who’s Doing the Romming?

Though this is a romcom, there is a fundamental disrespect for the institution of marriage from all three of the main characters. Marriage is a game for queer people and other people living on the margins to play. One gets married for money, or tax breaks, or green cards. Sometimes, presumably, love is involved, but that’s not necessary. Simon is the one who brings up the marriage idea first and is unthreatened by the idea, perhaps because he knows it doesn’t have the same sociocultural significance that it does for many heterosexual people. Marriage is one thing; commitment is a totally different one.

The idea that the wedding is not the basis for a happily ever after subverts the hetero romcom expectations, but the film does employ the love triangle aspect that we see in films like My Best Friend’s Wedding and Bridget Jones’s Diary.

The tension in the Wedding Banquet is who will win out in the end, Wei-Wei or Simon? Which is another way of asking whether Wai-Tung will keep his gay American dream that he’s already built with Simon or will he wreck it just enough to make his parents happy that returning to that life becomes impossible?

Wei-Wei is a wonderfully rich character. She is a well-trained painter who moonlights in whatever under-the-table gig she can find that keeps her rent paid (and oftentimes it’s not paid). Her family is from Mainland China (Shanghai), and her parents seem to be poor, working class at best. This is shorthanded as Wei-Wei telling Wai-Tung’s parents that it’s difficult for them to visit. Wai-Tung’s parents don’t ask for further details. An underlying dynamic is that Wai-Tung’s father is a retired general who fought both the Japanese and Communist armies in China. Their family then fled to Taiwan, where they raised Wai-Tung, and now enjoy an ability to visit the United States and return back home. In a perfect world, Wai-Tung would not have picked someone so unpolished, but they’re happy he’s picked someone who can at least speak Mandarin Chinese.

Wai-Tung is fortunate that his white partner encourages him to embrace his Taiwanese identity, and himself tries to learn about those customs and cultural practices. He hosts and cooks for Wai-Tung’s parents when they visit New York City. He is learning Mandarin Chinese. He fumbles through some of the traditional customs of greeting “parents-in-law,” such as offering gifts.

The film offers a number of shots that show just how lonely it must be for Simon, as well, to be in this situation. He is a trooper. He trains Wei-Wei in caring for Wai-Tung, and works in the background to make the visit go smoothly. Then, he has to sit back and watch as Wai-Tung’s gush over their gratitude to Wei-Wei for convincing their son to finally get married. They engulf her with love and drop corals and stones and cash in her lap to welcome her into the family. Eventually, even Simon’s patience runs out and he snaps at the pressure of being on the outside, looking in. (Wei-Wei does this, too, in her own ways).

Though Simon eventually earns a grudging acceptance of his own, the film ultimately splits the difference. Wei-Wei and Simon both win the guy in the end, which perhaps points to the ways that divergence from the family structure can be stomached, if the family remains intact (Han).

The Specter of HIV/AIDS

One of the things I most respect about Lee’s directing is how much of the texture of a gay man’s life from this era is actually in the film. The portrayal of Simon and Wai-Tung never feels forced or like a caricature. Part of that texture, of course, are the reminders of the HIV/AIDS epidemic which are scattered throughout the film.

For instance, Simon wears a Keith Haring “Ignorance = Fear” (1989) t-shirt, which incorporates Gran Fury’s iconic Silence = Death (1987) imagery and slogan. The first time that we see Simon, we see the t-shirt beneath his white coat. The first time we see him across from Wai-Tung, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is also in the room, a silent reminder that it permeated the lives and quiet moments of nearly all gay men at that time.

We also see, albeit very briefly, that Simon is an ACT-UP activist, and in one scene there is a throwaway line of dialogue where he tells a passerby on the street about “Monday night,” which is a reference to the iconic ACT-UP meetings that occurred each Monday evening at 7pm at the LGBT Center.

The act of Wai-Tung sleeping with Wei-Wei during their supposed sham wedding bothers Simon, but not as much as the fact that Wai-Tung had unprotected sex with someone else. This fact is the thing that finally puts him over the edge and causes an eruption in front of Wai-Tung’s monolingual (Mandarin Chinese) parents.

The gay characters, represented especially by Simon, are men who have had their lives shaped by the AIDS epidemic. They’ve likely had friends who have been sick or died, most in the primes of their lives. That feeling of precariousness is what makes their relationship so much more precious.

Wai-Tung, when he finally comes out to her, explains to his mother how hard it is for men like him to find someone. What does he mean by that? It’s hard for everyone, sure, but I think it’s hard for some gay men to find someone because of how many fewer gay people there are. And then when you do find one, it’s not a sure thing that that particular gay person will be a right fit for you. It’s actually a minor miracle that Simon and Wai-Tung, gay men in their 30’s in 1993 Manhattan — and we remember that each successive year until 1996 was worse in terms of deaths and new acquisitions than the year before — have managed to find one another, fall in love, and stay alive or healthy long enough to plan to build a future. So much in society tells them they shouldn’t count on a life together, but yet they do.

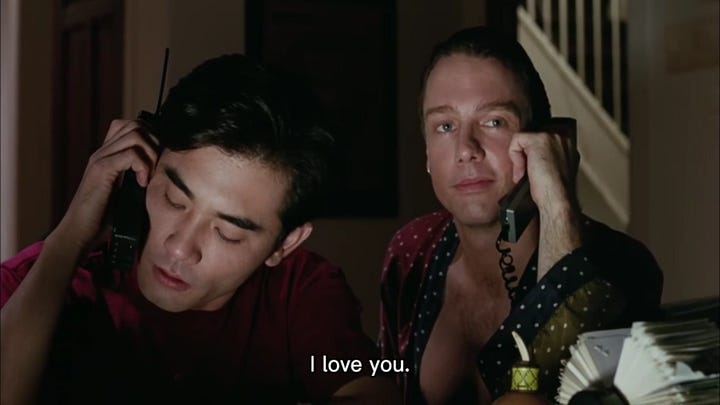

But it’s tenuous – so much so that when they say “I love you,” they cannot look at one another, and it’s mediated by a new cell phone and home phone. A locked landline, and a line that can roam.

Part of what makes Lee’s queer characters feel so real is that there are multiple things happening to them. Familial dramas, immigration issues, money problems, planning for a future that they fully want and expect to take part in. In the midst of the pre-HAART epidemic, many gay men were building their lives and trying to fall in love and dreaming about the future – all while fighting for treatments and drugs into bodies. That duality, of living life and a terrible intimacy with death, is crucial to remember about queer art from this time.

Truthfully, I’m surprised by how excited being engaged has made me. To adapt Grace Jones’ lines, we’re not perfect, but we’re perfect for each other. And it feels like we’ve both accomplished something that we never thought would be for us – we’ve found that person who we want to commit to for life.

I don’t know when people start to think about that stuff, but I know that growing up gay in the Bush era, you became convinced that getting married wasn’t for you. The alternative was to run away to the big city and build your new life there. Marriage be damned; there were bigger fish to fry, like finding someone you liked enough and who liked you enough to actually become your boyfriend. Like writing poems, or watching French New Wave films, or dancing at Big Chicks.

But then it sort of happens – you wake up one day, older, and realize you’ve met the right person. At least, that’s how it happened for me.

I was really moved by Simon and Wai-Tung’s relationship on this viewing because in some ways theirs is precisely the sort of partnership that I have always wanted for myself. Simon cares about Wai-Tung’s family and tries to engage his culture. Their life is filled with great friends and both are comfortable and thriving in the big city. They’re politically conscious, they fuck on the stairs, say I love you through the telephone. And all of this in a hostile world that insists on demeaning and invalidating their relationship. Marriage is one thing, but Simon is willing to stick around when things get really messy. And he has no other motive or incentive or legal obligation; he does so for no other reason than being in love.

Dallas and I are lucky. No matter what type of celebration or ceremony we choose to have, our parents and families will want to be there, and will be joyous. We don’t know quite what we’re going to do, but I can say with almost certainty that we will not be having a giant wedding banquet. Fun as that might look…

Thanks Jonathan for this great read! Congrats on your engagement. Also, I didn't expect to feel so identified with Wai-Tung with listening to voice notes while at the gym!